Summer Thunderstorms

Article for June/July 2024

If the clouds clear enough for some sunny weather this summer, it is likely that we still won’t see the end of the rain. Hot weather is often accompanied by a dramatic outro – the summer thunderstorm. Though we see rain throughout the year, summer is particularly known for thunderstorms. They can come on quite suddenly, heralded by a darkening sky and the low rumble of thunder that sees us scrambling to bring the garden chair covers inside before their inevitable soaking. In fact, it is precisely those warm temperatures that provide the perfect conditions for developing storms.

The Water Cycle

The classic water cycle shows us how heat from the sun evaporates moisture in the air, causing it to rise as gas until it cools enough to condense into water droplets and form clouds. Atmospheric instability, caused by a large difference in temperatures between the warm air near the earth’s surface, and the cold air high up, causes rapid rising and the building of massive cumulonimbus clouds that tower at heights of 500-16,000m (2,000-52,000 ft).

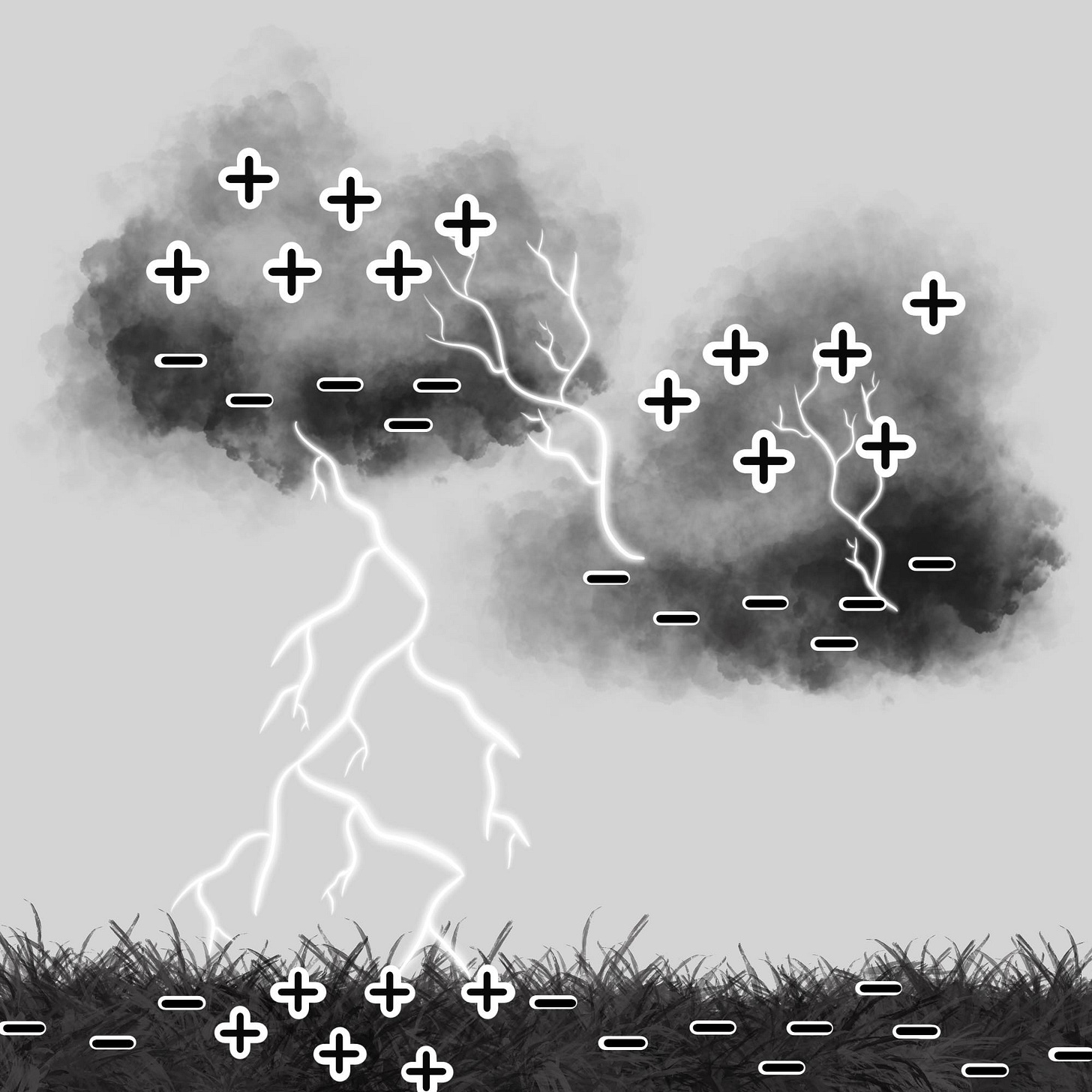

At the top of these clouds, it is cold enough for the water droplets to turn to ice. In the bustle of molecules, ice crystals collide with each other, knocking off electrons (tiny sub-atomic particles with a negative charge) which then gather at the base of the cloud. As the bottom of the cloud and the surround air becomes negatively charged, the top of the cloud becomes positive — this creates an ever-increasing electric field, just waiting for the moment to discharge.

As the bottom of the cloud and the surround air becomes negatively charged, the top of the cloud becomes positive — this creates an ever-increasing electric field, just waiting for the moment to discharge.

Lightning strikes usually arc from cloud to cloud, though when the negative charge at the bottom of a cloud is strong enough, it can be enough to change the ground itself positive, and this is when lightning strikes the earth. A bolt of lightning moves at 270,000mph at a temperature of 30,000°C – five times hotter than the sun. It is this incredible heat that causes the accompanying role of thunder. Air expands around the lightning strike, creating a shockwave that is heard as a thunderous boom. We can use the delay between the lightning strike and the thunder to estimate the distance we are from a storm; the longer the delay, the further away the storm is. Each second delay can be divided by three to give the estimated kilometres.

Though sometimes destructive, thunderstorms are beautiful wonders of nature. They can also help the environment. Plants need nitrogen to grow and, though it is found plentifully in the air, for it to get into the soil they rely on algae, bacteria, and lightning! The heat of a lightning strike bonds nitrogen and oxygen with moisture in the air, which then falls as nitrate-rich rain.

So, next time the sky darkens and the air fills with the sound of distant thunder, take a moment to marvel at the intricate and fascinating process that’s unfolding above. After all, summer wouldn’t be quite the same without the dramatic flair of its thunderstorms.

Sources and further reading: